Introduction and context of the project

1. ‘NON-BINARY Cross Space III’ has been acclaimed for its focus on adaptability and flexibility in domestic spaces. What inspired you to develop a project like this?

We tend to avoid using the word ‘inspiration’ when referring to something as complex as architecture. We would rather speak of influence or necessity. Let’s say that these two strategies of research and intervention within the existing built fabric stem from observing how ways of living have evolved dramatically over recent decades. We can no longer predict with certainty the specific future needs of those occupying a space.

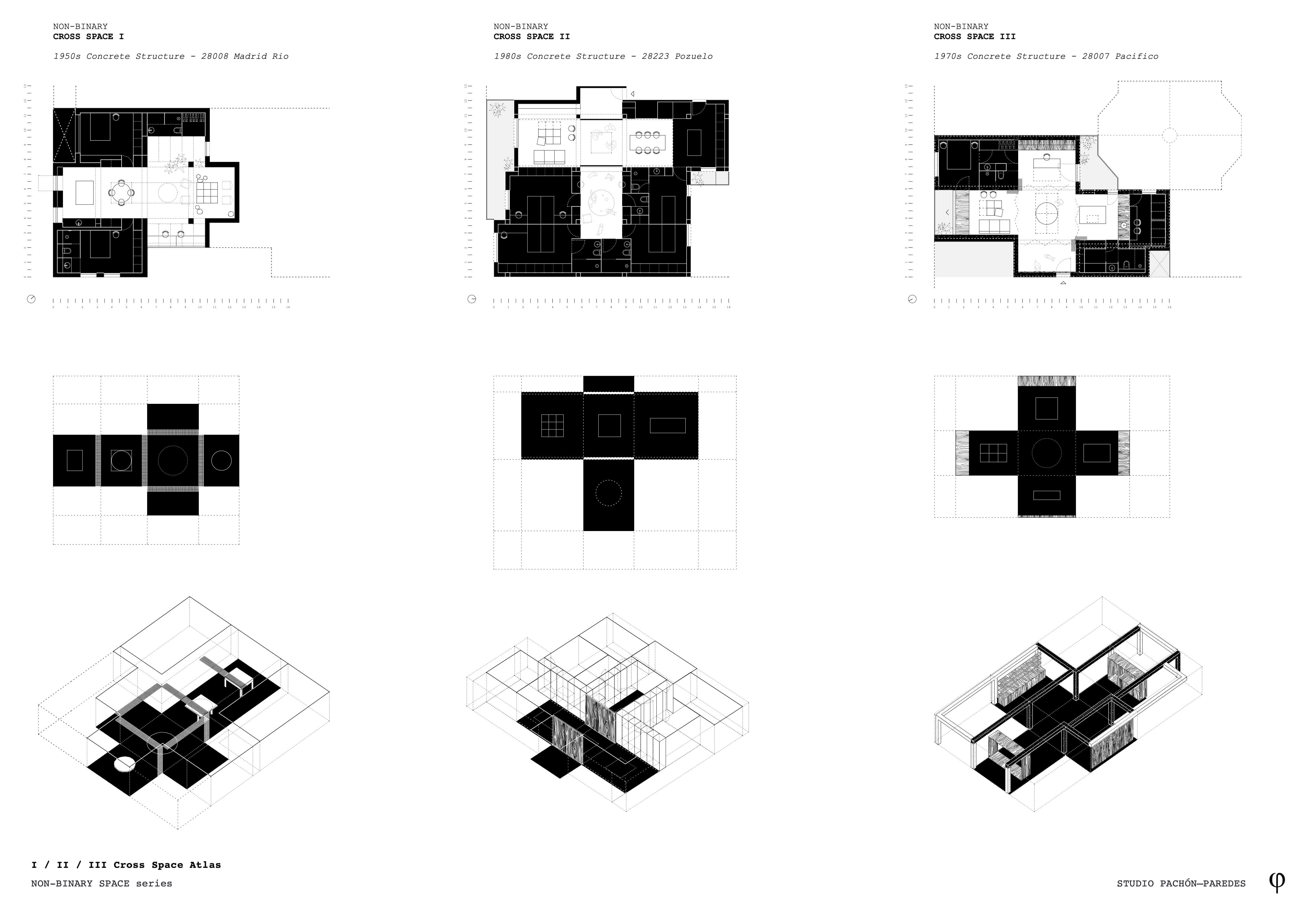

‘NON-BINARY SPACE’ is a cross-disciplinary research process that spans various scales, exploring the concept of an undefined habitat through the synergies between space, time, matter and energy. Its goal is to preserve the freedom of use, occupation, adaptation and interpretation of space by its users, cultures and socio-economic factors over time.

On the other hand, ‘CROSS-SPACE’ involves a series of transformations, adaptations, rehabilitations, and additions that are shaping a strategy for sustainable spatial occupation, inherent to the type of structure or infrastructure in which they are embedded.

2. The jury highlighted the importance of neutrality and freedom of use in your works. How did you manage to balance these concepts with the need to create a functional and liveable space?

For us, the key is to recognise that, on one hand, space is primarily ‘fixed’ and ‘static,’ although there are tools that can introduce some flexibility; and on the other hand, true flexibility and transformation come from the mobile and living elements (users, furniture, objects, plants, energy…). It’s important to understand that space must be designed in a versatile way, allowing for maximum flexibility and adaptability by its users with minimal intervention. This approach fosters an economy of resources and reduces the need for drastic changes over time.

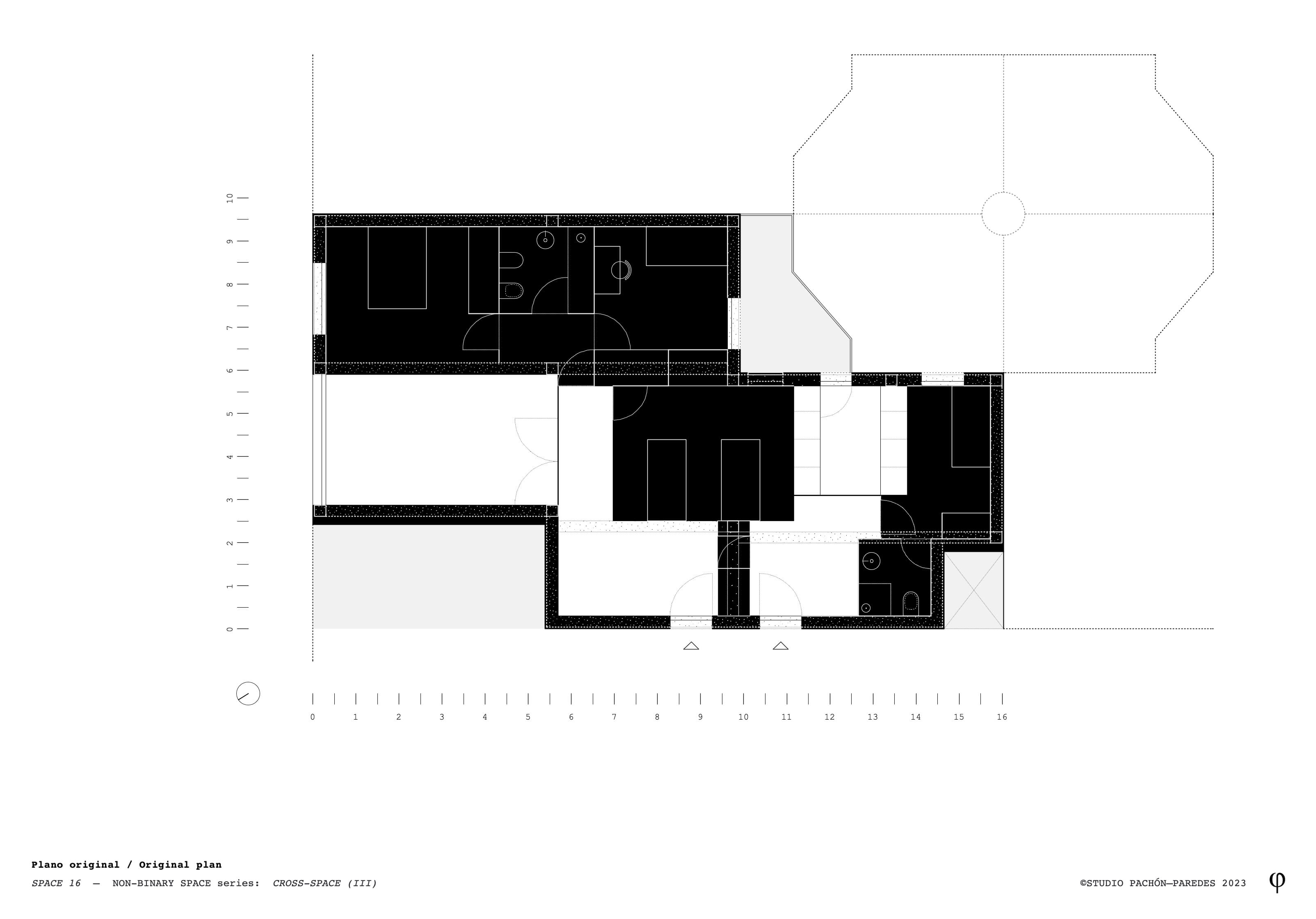

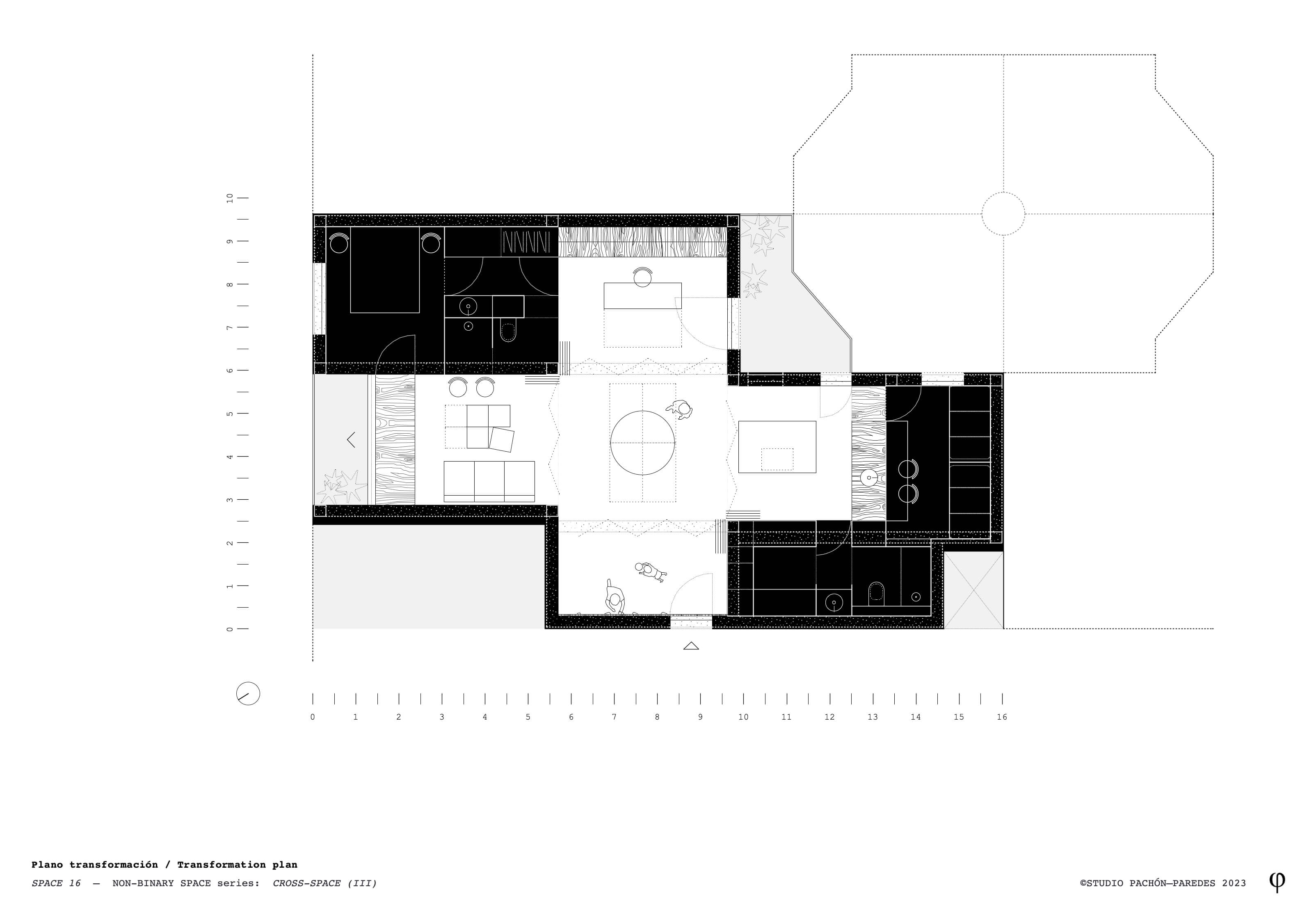

The occupancy strategy examines and interprets the potential of the structural grid created by the system to define two types of spaces: ‘Binary’ and defined spaces; and ‘Non-binary’ spaces, which are undefined, neutral and flexible Strategically, the minimum necessary defined spaces are planned and constructed in each project, creating a resulting void – an ‘unbuilt’ space – the ‘cross-space,’ which is undefined in nature. The resulting space takes shape depending on the structure being inhabited, with various quadrants, aisles, intersecting spaces, and adjacent or continuous areas. These can be understood (and used) as extensions, additions or transitions, enabling a timeless undefinition of spaces and their associated uses.

3. Could you tell us about the process of renovating the 1970s house in the Pacífico neighbourhood? What specific challenges did you face when working with an existing structure?

In this case, as in previous ones, the conditions of the façade, structure and orientation were very specific. The previous house was dark in most of its rooms, with no cross-ventilation or natural light from the south in the communal spaces. On the other hand, the clients’ financial constraints significantly limited the scope of the work.

Thus, the spaces were adapted to the dimensions, lighting, heights and construction limitations inherent in the structures and concrete dimensions that were prevalent in the second half of the 20th century in the expansion areas and outskirts of various Spanish cities. It’s not only a strategy for spatial adaptation and transformation but also a constructive and economic approach. The solutions implemented across the entire envelope are designed to make the most of the existing conditions of the structural foundations, slabs, columns, beams, openings and façades. The possibilities of the grid created by the structural system are analysed and interpreted to define: ‘Binary’ and defined spaces; and ‘Non-binary’ spaces, which are undefined, neutral and flexible

There is always a balance to be struck between adapting to the existing conditions and, at the same time, making the most of them – not just the limitations imposed by the structure, but also the façades, orientations, openings to the outside and pathways for ventilation and natural light. We worked in a holistic way, integrating aspects such as spatiality, thermodynamics, habitability, intimacy, versatility and economy.

Vision and conceptual approach

4. One of the key concepts behind the project is the idea of creating ‘neutral spaces.’ How do you define a neutral space, and why is it relevant in contemporary architecture?

A neutral space is one that is not predetermined by a specific function, use, hierarchy or material. An undefined, flexible and versatile space. One that can be easily adjusted, adapted and transformed by its inhabitant: using our own terminology, ‘NON-BINARY SPACES.’ It could be said that a non-binary space is a state of variable condition. A free-to-use space should neither be undefined, defined, general, neutral, nor specific; rather, it should have the ability to fluctuate over time.

In considering the response that contemporary architecture should offer to society, the final state of definition for the space – non-binary – should not be conditioned by the architecture itself, its elements, dimensions or rules associated with specific uses or typologies. It should aspire to maximum adaptability and flexibility in response to the changing nature of human behaviour over time, fostering flexible synergies that do not compromise the freedom of interpretation, use and appropriation by the users or social structures that inhabit it.

5. In your work, you touch upon theories of flexibility, hybridisation and adaptability. Could you explain how these theories influence your design approach and the creation of ‘NON-BINARY Cross Space III’?

Throughout the 20th century, similar relationships have been explored regarding the indeterminacy between space and function, or the capacity for change and variability that architecture can offer, freeing it from typologies or specific functions. Beyond specific practices, projects and theories, there are also spontaneously existing non-binary spaces in our way of living, in our infrastructures and in our culture and history. Thus, the term ‘NON-BINARY’ applied to architecture encompasses all spaces and architectural forms that lack a label, a specific architectural genre or a restrictive category, whether typological or functional. It also refers more freely to the changing qualities applied to space, bringing together and blending spatiotemporal, energetic or material concepts.

6. The project proposes an intervention that offers maximum adaptability to the changing behaviours of its users. What architectural strategies did you employ to achieve this adaptability?

The ‘unbuilt’ quadrants that make up the empty space of the ‘cross-space’ – free-to-use spaces – are designed as dynamic, fluid spaces: ‘street, square, public thoroughfare, collective and shared space.’ The nature of this space allows its users to inhabit and programme it, connect and integrate it, or easily transform it throughout the day, week, months or years, much like a public space in the city. In CROSS-SPACE (III), the main ‘façades,’ which define the four boundaries, incorporate elements that enable the programming and reconfiguration of each quadrant for various uses, such as culinary, office, sports or leisure activities. These elements include: appliances, installations and pantries; doors, hangers, climbing walls and sports equipment; radiators, air conditioning, doorways; tables, computers, screens, shelves and storage units…

On the other hand, the ‘binary’ domestic spaces are nestled within the perimeter, occupying the edges of the ‘cross-space.’ They support the undefined space while providing privacy. Thus, this ‘defined’ built boundary becomes the secondary façades of the domestic public space: bedrooms, bathrooms, wardrobes, installations, panelling, windows, doors, walls, terraces, etc. They function like ‘shops, premises, arcades, passageways, viewpoints, fences and gardens.’

Creative process and materials

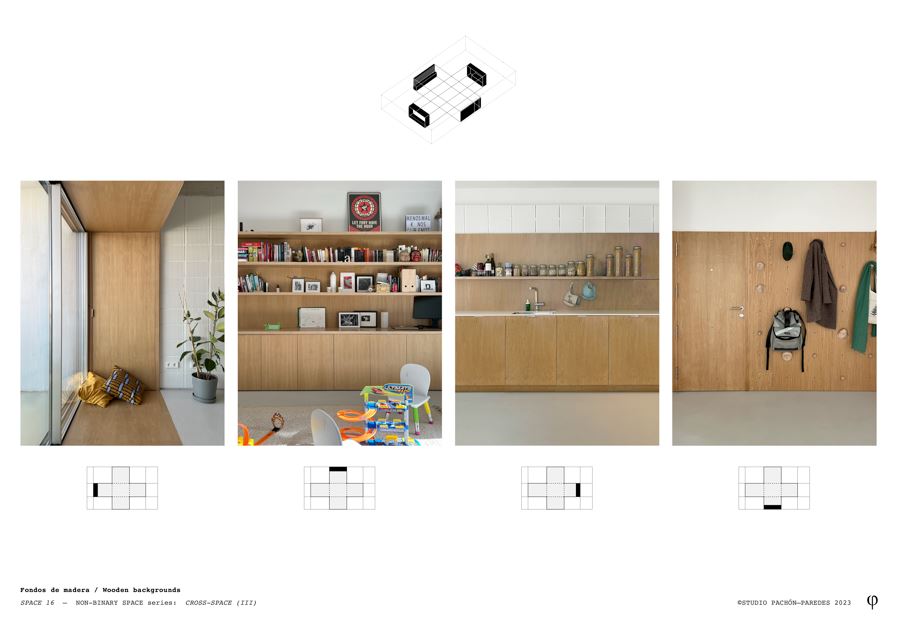

7. The use of natural materials that maintain neutrality is a key feature of the project. What criteria did you follow to select these materials, and how do they influence the perception of the space?

The ‘non-binary’ space must provide various thermodynamic possibilities, both passive and active, for its potential users. In this way, the necessary connections are freed up to allow for maximum adaptability in terms of natural light, ventilation and access to outdoor spaces, through the recovery and spatial connection of terraces that were previously removed. The material and construction treatment also addresses the undefined nature of the elements, aiming to remain neutral both in terms of the ‘visual/aesthetic’ and the ‘invisible/tectonic,’ with the goal of making the space as adaptable and accessible by current and future users as possible.

8. When talking about ‘non-intervention’ in the design process, what do you mean exactly, and how is this concept reflected in the final outcome of the project?

By ‘non-intervention,’ we mean the idea of not imposing a fixed function on the space through design. In practice, this means minimising fixed barriers and allowing the space to flow. Rather than filling the environment with partitions and fixed furniture, we propose a spatial platform that users can ‘inhabit’ and ‘complete’ according to their own needs, both now and in the future.

9. How did you integrate the existing structures into the final design without compromising the flexibility and neutrality of the space?

As mentioned earlier in some of the questions, the existing conditions and dimensions of the structural foundations of these concrete structures – slabs, columns, beams, openings and façades – are adapted and utilised. The possibilities of the grid created by the structural system are analysed and interpreted to define: ‘Binary’ and defined spaces; and ‘Non-binary’ spaces, which are undefined, neutral and flexible

A distinctive feature of this project was the beam and column structure, which had an unusual characteristic: a shift in each quadrant, creating a stepped effect. Instead of concealing this feature, we chose to emphasise it by applying a colour code to the concrete in each shifted section. In a way, this creates a connection between the user of a flat and the overall structure of the building that supports it.

Impact and reflection

10. The project seems to challenge traditional notions of domestic space. How do you think this approach could influence future rehabilitation projects and residential architecture in general?

On one hand, it seems to challenge the traditional foundations of domestic space, but perhaps it’s more accurate to say that it challenges the notions of domestic space from the 19th and 20th centuries. ‘Tradition’ is a word and concept that greatly appeals to us. There are domestic spaces from certain historical periods and cultural contexts where this type of space already existed naturally. An example would be the traditional Japanese house, the layout of interconnected rooms in Palladian villas or Renaissance palaces, or the farmhouses and barns prior to the 19th century, where the entire family combined work, living, education and more.

Fortunately, many professionals and colleagues are researching and working on these topics from different perspectives, each with their own unique approach. We believe this generation can inspire other professionals, institutions and disciplines to recognise the need to free spaces from specific programmes, paving the way for more undefined, flexible configurations that are timeless, durable and ultimately sustainable. The goal is to encourage spaces that can evolve over time with minimal changes, rather than constantly changing their use and consuming far more resources.

11. Society increasingly demands flexibility and adaptability in the spaces it occupies. What role do you think architecture will play in meeting these demands in the coming years?

People have one life, but spaces and buildings have many, diverse ones. Architecture will need to respond by designing environments and spaces capable of evolving without the need for major works and interventions, anticipating obsolescence, entropy and adapting to changing lifestyles. To achieve this, it’s essential to work with principles such as neutrality, temporality and timelessness, as well as the reuse of existing resources and elements, which will facilitate the adaptation of spaces to new uses and contexts. Thinking holistically about the integration of space, time, matter and energy, with the latter understood in all its meanings.

12. Finally, how do you see the evolution of STUDIO PACHÓN-PAREDES following this award, and what new challenges or projects do you have in mind for the near future?

This recognition encourages us to deepen our research into NON-BINARY SPACE and CROSS-SPACE, exploring their application to different environments, types of structures, and scales, as well as other dimensions and interpretations. We want to continue exploring new domestic or work-based typologies, even within public facilities, where polyvalency, flexibility, neutrality and adaptability take centre stage once again.

13. Is there any aspect of the ‘NON-BINARY Cross Space III’ project that you would like to highlight for our readers?

We would highlight that it was one of the most minimal projects, with the smallest surface area and budget of all those presented –ultimately, it’s a 100m² renovation. We would like to thank the jury for recognising projects of this scale and magnitude, understanding that the impact on new ways of living doesn’t necessarily have to be linked to large buildings or interventions. On the other hand, we would like to point out that the project is part of a series of projects. Together, they form the real project: a series of transformations, adaptations, rehabilitations and additions that are shaping a strategy for spatial occupation, inherent to the type of structure or infrastructure in which they are embedded.

14. What advice would you give to other architecture studios looking to explore flexibility and adaptability in their projects?

We would encourage them to question pre-existing typologies, revisit the spatial traditions of our history and environment, and analyse the dynamics of change and social structures. They should consider new models that blur the boundaries between domestic, work and even leisure or desire, while integrating all the necessary disciplines and stakeholders. Ultimately, it’s about working with the past, present, and future in the most transversal way possible. For us, it’s essential to embrace the uncertainty of the world we are living in, leaving room for the unpredictable, controlling only what is necessary and creating environments capable of accommodating multiple scenarios and adapting to the social, cultural and technological transformations of the future.