The Architectural Revolution

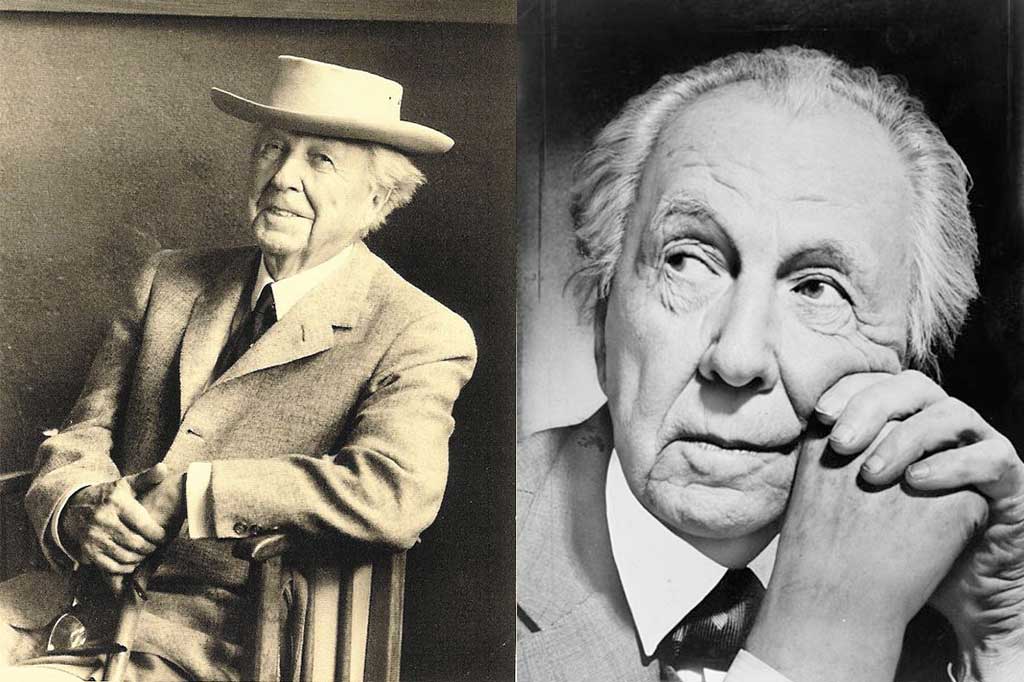

Elizabeth Gordon, one of the most influential interior decorators in American history, when referring to Frank Lloyd Wright would use one word: “God”.

The relationship between Frank Lloyd Wright and Elizabeth Gordon developed through a mutual understanding of form and place, their aim was to reinvent American architecture and give it an identity apart from the existing buildings based around their designers’ roots in old Europe. Lloyd Wright’s early works, complementing the roaming countryside of his native Wisconsin would blend into the scene and take the place of natural objects, for artists, the works of Frank Lloyd Wright are as natural as the autumnal leaves on the ground.

*Image: Pinterest

*Image: Pinterest

At the time Lloyd Wright began to put his style into practice, houses were inconsistent due to their origins being derived from many different countries and architectural philosophies of Europe and styles and not suited to the new, expansive landscape on prairies of America.

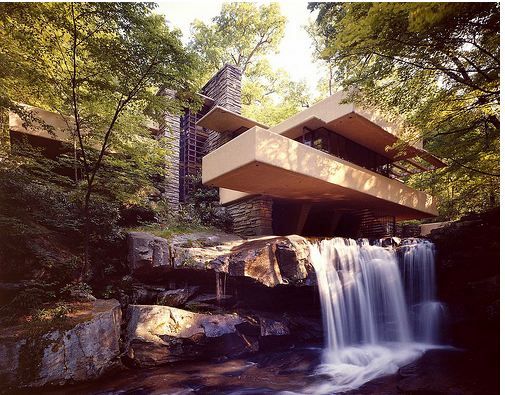

“No house should ever be on a hill or on anything. It should be of the hill. Belonging to it. Hill and house should live together each the happier for the other.“

Frank Lloyd Wright.

So the challenge was to homogenise American architecture and create a style that would be seen as ubiquitous across the land, complementing the countryside and blending into the scene. Surprisingly then, it was not Europe that would influence American architecture in the coming years, but Japan.

“At last I had found one country on earth where simplicity, as nature, is supreme.”

Frank Lloyd Wright

To do this he designed creative rules that architects could follow to achieve consistent design. Lloyd Wright developed an architectural grammar, which would be explicit in mapping out the design of new houses; all houses would have foundations containing four elements, a basement is obligatory (except in house with double or triple height living spaces), the fireplace would form the focal point of a house, with all extensions radiating from this point out into the prairie. These rules would dictate not only the shape of the houses, but also the shape of the revolution he would champion, and as a result, many aspects of American culture itself.

Talisien West

There are various structures, by Lloyd Wright himself and also by other architects of the time that portray the Prairie style perfectly, but none more so than Taliesin West (Welsh for “shining brow”). This house was used as Lloyd Wright’s winter retreat, and also as his architectural school, embedded into the Arizonan landscape, this rustic force-majeure was a statement of how form can be used to not only match its surrounding, but to both complement and improve it.

There are various structures, by Lloyd Wright himself and also by other architects of the time that portray the Prairie style perfectly, but none more so than Taliesin West (Welsh for “shining brow”). This house was used as Lloyd Wright’s winter retreat, and also as his architectural school, embedded into the Arizonan landscape, this rustic force-majeure was a statement of how form can be used to not only match its surrounding, but to both complement and improve it.

“The good building is not one that hurts the landscape, but one which makes the landscape more beautiful than it was before the building was built.”

Frank Lloyd Wright

Having first encountered the site, sleeping alongside local herdsmen in temporary pyramid-like structures, Lloyd Wright was inspired to build a retreat here, away from the deep snows of Wisconsin. The forked, straight lines of Taliesin mimic these pyramids, intimating the life of the people from this region. The house itself during Lloyd Wright’s life was as ephemeral as the structures that begot its design. Each summer he would take away walls, add new steps and use the house as a test bed for his new ideas. This is the reality of the structure, is constantly moving and changing, nomadic like the people of the desert around it.

Having first encountered the site, sleeping alongside local herdsmen in temporary pyramid-like structures, Lloyd Wright was inspired to build a retreat here, away from the deep snows of Wisconsin. The forked, straight lines of Taliesin mimic these pyramids, intimating the life of the people from this region. The house itself during Lloyd Wright’s life was as ephemeral as the structures that begot its design. Each summer he would take away walls, add new steps and use the house as a test bed for his new ideas. This is the reality of the structure, is constantly moving and changing, nomadic like the people of the desert around it.

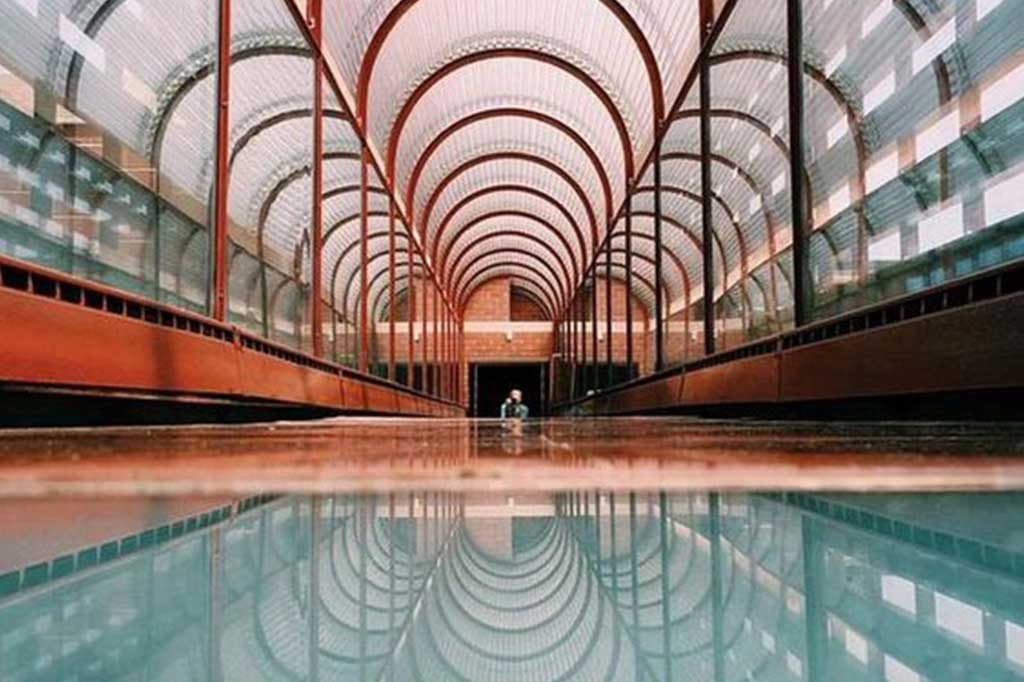

Architectural Interior

An anecdote upon coming close to finishing one of his works, was that Lloyd Wright was so obsessed with consistency throughout the interior, that he designed his client’s wife’s dressing gowns. Wright aspired to not only recreate the form of American housing but to create an interior and exterior to encompass a whole environment. He created stained-glass windows, flooring and carpets to brief, often asserting his own interpretation according to the client. His interiors would incorporate natural light through light panelling, features would be integrated into the design, vertical elements such as chimney stacks would synchronise with horizontal lines to draw the eye around the room.

*Image: Pinterest

*Image: Pinterest

Being an advocator of Japanese architecture and Feng-Shui, Lloyd Wright also included water moats around a fireplace, contrasting the fundamental elements of fire and water. Alongside the geometric features made available by pouring concrete, Lloyd Wright’s interiors were dramatic and thought provoking.

Guggenheim

Later in life, in 1957, Lloyd Wright completed his most memorable work in the centre of Manhattan. The Guggenheim museum was a testament to the flair that Lloyd Wright had inhibited during his earlier career, unleashing curves and lines that would imprint themselves upon the mind. For its time in 1959, this was the forefront of architecture, locals were divided by the sheer audacity of this building, the spiral, snail-shell gallery, was a completely new architectural experience for architects.

In fact, that the building inhabits artworks was for many years seen by artists as curse; they felt the building overpowered even the artworks of Picasso and Rembrandt, and being a constant graduated floor, viewers complained that they were not able to fully appreciate the art they were viewing. This stands as a testament to the sheer beauty of the Guggenheim, an artwork greater than that to be found inside.

This last work of the revolution begot what was to come following Frank Lloyd Wright’s revolution; The Guggenhiem of Bilbao; La Ciudad de las Artes y Las Ciencias of Valencia; The Weisman Art Museum of Minneapolis. Each themselves flowing and modern structures reflecting the lines of the Guggenheim, New York, but each containing exhibitions that betray the exterior, lacking in content, they are white elephants that leave visitors with a sense of emptiness.

This last work of the revolution begot what was to come following Frank Lloyd Wright’s revolution; The Guggenhiem of Bilbao; La Ciudad de las Artes y Las Ciencias of Valencia; The Weisman Art Museum of Minneapolis. Each themselves flowing and modern structures reflecting the lines of the Guggenheim, New York, but each containing exhibitions that betray the exterior, lacking in content, they are white elephants that leave visitors with a sense of emptiness.

Revolution

What Frank Lloyd brought to architecture will remain for many years to come, if not in design then in theory. The revolution, like the works of Lloyd Wright himself remain ephemeral, and the post-modern shifting of the Japanese philosophies of Lloyd Wright will continue to bear new paradigms that reflect landscapes. It is not so much “a style, but style” in the words of Lloyd Wright himself, meaning the structure itself is less important than the place it inhabits. And if there is a truth about Lloyd Wright’s architectural revolution, it is this.

What Frank Lloyd brought to architecture will remain for many years to come, if not in design then in theory. The revolution, like the works of Lloyd Wright himself remain ephemeral, and the post-modern shifting of the Japanese philosophies of Lloyd Wright will continue to bear new paradigms that reflect landscapes. It is not so much “a style, but style” in the words of Lloyd Wright himself, meaning the structure itself is less important than the place it inhabits. And if there is a truth about Lloyd Wright’s architectural revolution, it is this.